|

EUROPEAN EXTREMITIES

In this article the author, coming from one

European extremity to the other, tries to give an impression of the

effect which Portugal has on visitors from colder climes

by

RICHARD D. LEWIS

FOR many centuries the continent of Europe

has been the centre of the world stage. The Greek, Roman and western

civilisations have been instrumental in writing the greater part of the

history of the worId as we know it. Europeans opened up the continents

of Africa, America and Australlasia and put them on the map of the world.

Even in Asia – the only continent where European influence was not

decisive – there are large areas which owe their present development

mainly to British and Portuguese initiative.

Europe's dominance in world history is no

accident. There are many factors involved – geographical, historical,

ethnological and climatological – which combined to oblige Europe to

play her role. It is a fascinating subject which can be discussed at

Iength in articles other than this.

Europe might be seen as a prolongation of

Asia to the west. The eastern face of Asia, running down from the

Berling Straits through northeastern Siberia, China, lndochina and

Malaya to Singapore, represents a Iand mass of astonishing length and

substance. Turning west, we find that this land mass begins to decrease

gradualIy as we traverse the Middle East and Russia. It narrows rapidly

when Europe proper is reached, finally tapering off to a watery end a

few miIes to the west of Lisbon.

The last few thousand years have witnessed

the tendency of peoples to migrate towards the west. We can assume it

was a selection of the more hardy and vigorous Asian tribes which

eventually made the arduous journey through what now is Russia to

explore little-known Europe beyond. The narrowing down of the continent

ultimately threw these adveuturous peoples together more closely than

the vast wastelands of Asia ever could have doe. The final full stop

reached in the Iberian peninsula set the stage for a European

melting-pot which was in a relatively short time to produce a blend of

races and types which would exceed anything the world had seen in terms

of energy and mobility.

Portugal, both on account of her

geographical position and heI historical development, is essentially

European. Whilst not so involved in European affairs as such central

states as Germany and France, she nevertheless has a clear roIe to play

as Europe's eye to the west and particullarly south-west. Anyone living

in Portugal is constantIy aware of the nation's consciousness of her

historical mission.

Prior to coming to Portugal, I Spent several

years in a country which is

/ 112 /

very far from the banks of the Tagus and yet is still Europe – at its

other extremity. Just as Portugal is the westem outpost of Europe, it is

clear that our continent must have an eastern outpost aIso. Somewhere,

Asia comes to an end. Then you have Russia. After that you have Europe.

And Europe begins in Finland. Prior to coming to Portugal, I Spent several

years in a country which is

/ 112 /

very far from the banks of the Tagus and yet is still Europe – at its

other extremity. Just as Portugal is the westem outpost of Europe, it is

clear that our continent must have an eastern outpost aIso. Somewhere,

Asia comes to an end. Then you have Russia. After that you have Europe.

And Europe begins in Finland.

I often woonder what picture the Portuguese

have of this country, so different from their own, and in many ways so

similar. There are no two western European countries so widely separated

as Portuga!l and Finland. They are literally the two extremities of our

continent. There is consequently little interchange of visitors between

the two countries.

Finland is 4 times as large as Portugal, but

has a population of only 4 million. Its capitall, Helsinki, is about

half the size of Lisbon. Apart from Iceland, it is the most northerly

country in the world, has 60.000 lakes, and over 70 percent of its total

area is covered by forests. The people are of Finno-Ugrian stock, being

in the main power fully-built, fair-haired and blue-eyed.

The Portuguesa visitor to Finland would be

impressed by its western aspect. The result of centuries of annexation

by Sweden and Russia is the emergence of a modern state with a

strongly-marked individuality and a clear-cut western culture. The lake

scenes, the saunas, the reindeer represent the perennnial charm of old

Finland as it is sung in her rich folklore. The other side of the

picture – the new ultra-modern Finland with her architecture and

hospitaIs, factories, technical schools, conference halls, progressing

industries and jet airliners reflects a new and more vigorous appeal of

this eastern outpost of this western continent.

In 1962 many organized groups of Finnish

tourists visited Portugal. Swedes, Danes, Germans and English are the

northerners who most frequently are seen in Lisbon, but with the

improvement of air communications and the shrinking of distances,

Portugal is rapidly becoming accessible to even the furthest nordic

peoples.

The climate, of course, is always the first

topic of conversation, and for the sun-starved Finns, Swedes and English

Portugal need have nothing further to offer for the first few days.

Northerners, however, are avid readers, and one finds that the Finns and

Swedes particuIarly have spent many of their long nights during the

previous winter familiarizing themselves with many aspects of Portuguese

life, history and culture. After three or four days in the sun, they are

eager tu get about.

Here perhaps we touch upon Portugal's forte

as a tourist country. There is an incredible amount to see in a small,

compact area. Wherever the country is destitute of wealth, it is rich in

history. Within a few hour's striking distance of Lisbon is the famous

battlefield of Aljubarrota, where 6000 Portuguese infantry smashed the

might of the Spanish army against unbelievable odds and established the

most brilliant dynasty that Portugal was too have. Batalha monastery,

one of the world's most attractive Gothic constructions, today marks the

triumphal spot. Within a few miles of this birthplace of the Portuguese

nation are Obidos, a magnificent example of a mediaevall walled town and

favourite spot of Portugall,s monarchy – Fatima, of pilgrimage fama –

Alcobaça with its beautifull Cistercian monastery where for Iong years

the Bernardine monks experimented with agriculture and rulled the area

which even to-day is prosperous on account of their efforts.

The Nordic peoples, with their lack of old

buildings and the English, with their sense of history, are invaIiably

fascinated by the abundance of Portugals structures from bygone days.

Mafra, Evora and Santarem, again alI an easy day's excursion from the

capitail, perhaps offer more in terms of interest to visitors from the

north than they would for tourists from the southern European countries.

Sintra, just outside Lisbon, has traditionally mesmerised theEnglish,

while Finns, Swedes and Danes alike are intrigued by its fauna and air

of unreality.

The guests from the other end of Europe find

that Portuguese food rarely disagrees with their stomachs. The hot, dry

cuisine, with its absence of oil, includes several interesting

delicacies – excellent chicken and pork, fish soups on the Tagus, bean

cakes at Torres Vedras, eel stew at Santarem, squid over the rival,

baked rolls at Coimbra, good red, white and green

/ 113 /

wine everywhere. The variety is certainly greater than in the northern

countries and most northerners, after a certain initial timidity, take

full advantage of it.

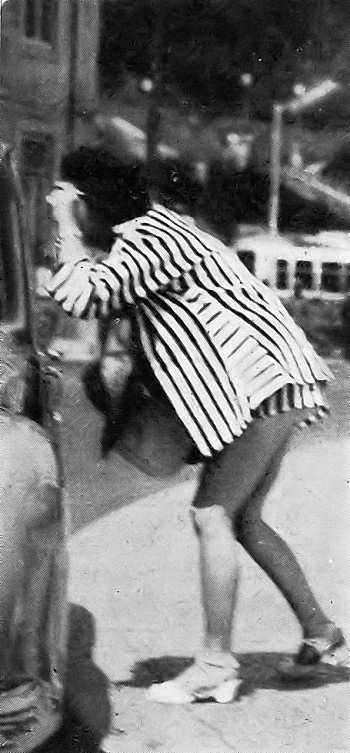

Finally, one must not forget that the city

of Lisbon, one of the most beautiful and individual of southern European

cities, is in itseIf a spectacle in northern eyes. Its warm air, bright

lights, breath-taking panoramas and lively inhabitants are a constant

entertainment for visitors from duller and colder cities. For many

northerners it is a pleasure just to walk down a Lisbon street wearing a

coloured shirt. Or to sit at a table outside on the pavement on the

Avenida de Liberdade and sip a port and watch the crowds go by. To sit

in the sun when they feeI like it and have a swim when they feel like it

and take a drink when they want to are luxuries to which they are not

accustomed at home. They are such simple things, which Italians,

Spaniards and Portuguese take for granted, and yet they constitute a

great attraction for the northern visitor. Finally, one must not forget that the city

of Lisbon, one of the most beautiful and individual of southern European

cities, is in itseIf a spectacle in northern eyes. Its warm air, bright

lights, breath-taking panoramas and lively inhabitants are a constant

entertainment for visitors from duller and colder cities. For many

northerners it is a pleasure just to walk down a Lisbon street wearing a

coloured shirt. Or to sit at a table outside on the pavement on the

Avenida de Liberdade and sip a port and watch the crowds go by. To sit

in the sun when they feeI like it and have a swim when they feel like it

and take a drink when they want to are luxuries to which they are not

accustomed at home. They are such simple things, which Italians,

Spaniards and Portuguese take for granted, and yet they constitute a

great attraction for the northern visitor. |